The first thing to realise is that creative writing is something of a drug. And like all addicts, budding writers, who keep their activities a murky secret, need a support network that treads a fine line between encouragement, understanding and brutal character assassination. For many of us, this is the Writers Workshop, an institution that strikes fear into the heart of anyone who has tried to write something other than a work email or a letter appealing against a parking fine. Many writers fall at this first hurdle, when, having been brave enough to submit their early, faltering efforts to the scrutiny of their peers, they are left shell shocked at the realisation that not everyone agrees with them that they have a rare talent that should be not only nurtured, but celebrated. Shouted from the rooftops, in fact.

The first time this happens, and you sit there, your smile becoming ever more forced and rictus like, as each sentence of the judgement of your friends and colleagues strips away another layer of self respect and self esteem, is a life changing moment. Your stare becomes glassy eyed, your eyes vacant and slowly and steadily you retreat back into some terrible protective shell, nodding wisely at every acid comment, every slash of the knife. Not listening behind a certain point of maximum pain, but just waiting for the whole ghastly experience to be over.

Why on earth would anyone put themselves through this more than once? And indeed, many people reach the same conclusion. They put it down to experience and vow never again to entertain such obviously deluded ideas about their own abilities. And they never come back. Some of them end up as the pub bore, always ready to burden their chums with their opinions about cultural products, self appointed experts on all the different forms of narrative experience. They refer frequently to their writing, usually as a prequel to their favourite subject, the evil of literary agents and the publishing industry, who, know nothing about the craft of writing but are only interested in selling, shifting units that are essentially the same as baked beans in the supermarket. They bore on about the hundreds of times JK Rowling got rejection slips. All this to subtly imply that genius such as theirs is routinely ignored by the lesser drones of an industry that represents the general decay of western cultural production. Others never mention it to anyone. They spend their life reading voraciously and watching box sets, silently brooding, while thinking, “It could have been me.”

Most of them manage to go on with their lives, some of them making a useful contribution to society. Some of them even become OFSTED inspectors, convinced that their frequent use of fronted adverbials and semicolons in their writing should have protected them from criticism. They will spend the next thirty years of their professional lives taking revenge on schoolteachers with a similarly sloppy approach to the craft of writing.

How to avoid such a fate? I’ve had quite a lot of experience of the dreaded writing workshop, in different groups and in different settings. Here are some basic rules that have emerged from my experiences. I’ve divided them into two sections: For Writers and For Critics.

For Writers

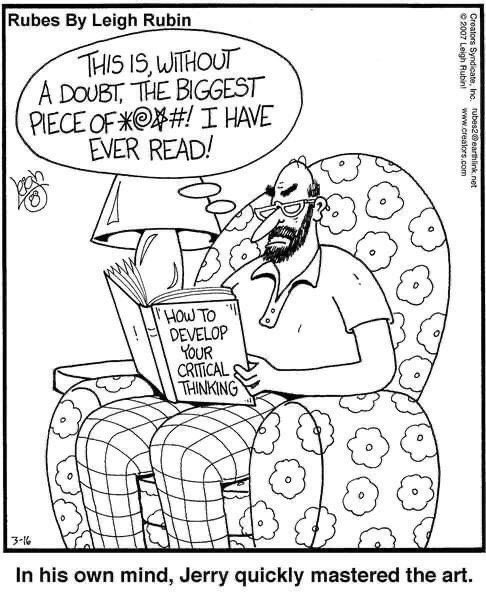

1. All First Drafts Are Shit

In the words of one of my esteemed tutors, All First Drafts Are Shit.(Or maybe they said, “All your drafts are shit” No, I really must work on this Imposter Syndrome thing) It’s a simple enough statement, but one that’s worth remembering. If your submission to the group is relatively unworked ( and weekly deadlines mean that it almost certainly is) you’re going to get a lot of critical feedback. Because all first drafts are shit. Listening to the feedback is one way of beginning to make them a little less shit.

2. The Reader is Always Right.

Until they’re actually wrong. (see 3 below) If one of your readers is telling you they didn’t like some aspects of your piece, please, before you open your mouth, remember that they are telling the truth and only they can know. It’s not an episode of Traitors where they are trying to double bluff you. They didn’t like it. And nothing you can say – no explanation of what you were trying to achieve – can make any difference to that. You have a choice of possible ways to respond. One way makes you look like a twat – and remember, it’s important, if you want to try to have a long run in the same group of writing buddies, to try to preserve some sense of dignity and humanity. That way is to argue. When you do this, you are basically saying that the reader is a moron because they did not get what you were trying to do. Hmm, how can I put this politely? Might it not be possible, nay, likely that they didn’t get it because you didn’t write it well enough? Worth considering, n’est-ce pas? The second way is much more straightforward. Just listen. Make some notes. And then go away and think about it.

3. Except when it comes to Literary Criticism

The plot thickens when their feedback strays into literary criticism, as it often does. As soon as they step onto that particular thin sheet of ice, well then you’re into the area of discussion, debate, argument. Because in trying to analyse why the writing doesn’t work, they will often get it wrong. And then you can really go for them….

4. Shut the Fuck Up.

Some writing workshops have formalised this so that is a key part of how feedback works. The person receiving the feedback is not allowed to respond, whether it’s asking or answering questions, or offering explanations. It is formally understood by all, that it’s the people offering the feedback who hold the floor. Given the fact that, in most cases, this process involves real human beings, this is harder to achieve than it sounds. In my experience, having silence as an unbreakable rule is the only way to make it work. I still feel myself going red and feeling uncomfortably hot under the collar when I recall some of my intemperate responses to feedback I didn’t agree with. Once again, if you value your reputation and want your membership of the group to continue profitably, just zip it, at least until you get home when you can offload to your long suffering partner about the heavy cross you have to bear in being an unrecognised genius surrounded by fools.

5. RASB

This acronym was, pleasingly, going to be Rasberry, but by the time I got to the letter E, I came over all tired and had to have a lie down.

Recognise the agony of releasing your work in progress into the world. The minute you do that, it’s not exclusively yours anymore. It’s remade afresh every time someone starts reading it. Because those pesky readers will insist on bringing their own stuff to the party, sometimes, or so it seems, wilfully misinterpreting what you’ve written. There is nothing more sobering than realising the yawning chasm between what you think you’ve written, and what the reader has read. If this sounds familiar to you, go back to rule 2 and have a little think. Giving your WIP to someone is a Revelatory Act of Supreme Bravery. It’s been your dirty little secret for so long and while it’s a secret, you can continue to live with the fantasy that it is good and you are a genius. Sending it into the world is the first and the decisive step in destroying that.

6. It’s OK to disagree

Notwithstanding rule 2, sometimes the feedback you get is wrong, or unhelpful, or does not have to be acted upon. How do you know which feedback is valid or important, and which is just the reader’s expression of personal taste? If you only have one or two readers providing feedback, then this is a difficult judgement and, in the end, all you’ve got to go on is your instinct. Does the feedback strike a chord with you? Does it chime with previous comments that have been made about your work? If it doesn’t, it may not be essential to enact it. After all, the next person who reads it may directly contradict the previous reader. You could spend all of your time chopping and changing, on the back of every successive reader’s comments, and end up exactly where you started.

7. Do The Maths

If you give your precious WIP to twenty people and nineteen come back and say that the opening chapter was slow and boring, then it’s not rocket science to think that you need to edit the first chapter.

Volume of feedback pointing out the same weaknesses is to be ignored at your peril. They haven’t all got together to plan your psychological destruction. Suck it up and make the changes.

8. Know Thyself

Try to use the experience to come to some overall understanding of your modus operandi as a writer. What is your usual model of working? What are your strengths and weaknesses? How does this compare to that of your fellow writers? The more of a handle you have on your preferred methods, the quicker you will be able to recognise the valuable things all of this feedback is telling you. And, the things that are, ahem, nonsense.

9. It’s Good To Talk. ( see 4 above)

Writing is essentially a lonely pursuit. Most writers, when they have finished something, are gripped by a powerful need for readers. Writers have laboured long and hard alone, thinking about the story, characters, themes, structure, voice etc. The list is endless. There’s always something to get wrong. And just like a football manager interviewed straight after the final whistle, writers are invariably unreliable witnesses when it comes to their own work. That was never a penalty! (After opposing forward has been subject to grievous bodily harm in the six yard box) But there are two different kinds of talk, each one essential for the writer. The first is forensic, critical feedback, which can be brutal and difficult to take. In this, the writer must shut the fuck up and listen. The second is akin to therapy. Writers want to talk about their work in progress endlessly and obsessively. They are gripped by a burning need to explain. They are compelled to share with fellow writers, or other keen, reliable readers, what they were trying to do, how they were trying to do it, and why. In this sense, I am convinced that when Coleridge wrote the Ancient Mariner, he had a writer in mind. The opening verses tell of a strange, wild eyed sailor, who randomly forced himself and his story on any unfortunate soul he meets. (In this case, a Wedding Guest)

It is an ancient Mariner, And he stoppeth one of three.

‘By thy long grey beard and glittering eye,

Now wherefore stopp’st thou me?

He holds him with his glittering eye—

The Wedding-Guest stood still,

And listens like a three years’ child:

The Mariner hath his will.

The Wedding-Guest sat on a stone:

He cannot choose but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed Mariner.

“He stoppeth one of three” and then he proceeds to bore the listener to death by telling him his story. Obviously a frustrated writer looking for a publisher/ agent.

If you’re working with a group using the Shut The Fuck Up model of interrogation, you must find another outlet, where you, the writer, can talk discursively and in an unrestrained way. Unless you’ve got very understanding friends or a saint of a partner, this has to be with someone who is tolerant of your need to obsess about your work in progress. Often, the only way of managing this is in a quid pro quo arrangement with a fellow writer. One week they listen to you droning on about your WIP, the next week you return the favour. I would go as far as to say that having a regular session for 15 minutes where people tell you how great the WIP is an essential prerequisite for emotional and psychological well being. This what pubs were invented for. Just be aware that, on its own, it’s also a routine guaranteed to ensure your writing doesn’t get appreciably better. And, incidently, ensuring that you quickly run out of friends But you’ll have a nice warm glow of well-being about you, so who cares?

10. The Shit Sandwich.

(Please note: I avoided the temptation to add an illustration)

It’s basic human psychology that people will only listen to criticism about their work on the back of praise that’s been laid on with a trowel. So if you are trying to help out a fellow writer, remember that your points of criticism must not only be specific and proportionate, but they must be heavily outweighed by all the good things you’ve been able to say about the work. If you are the person delivering the feedback you’ve got to be prepared to do the work and find genuine things to praise and be enthusiastic about. Let’s be nice to each other. But actually, the metaphor doesn’t really stand up. Because, no matter how nice the bread is – sourdough, brioche, perhaps a nice juicy, garlicky focaccia – at some point you’re going to have to eat some shit. And in reality, the filling of this particular sandwich, while it may not be palatable, is actually good for you. Maybe it should be the Cod Liver Oil sandwich.

11. Sleep On It.

The hurt of criticism is real, but the sting fades eventually. Embrace the pain. After all, like real pain and the red, angry inflammation it produces, it’s a sign that the body is working to process it. Here, it’s also a sign that you care about it, which is an essential precursor to good writing. Do the same with your mind and your heart, and let the feelings stew for a while. When you’ve done that, it’s much easier to a) hear the detail of what has been said, b) decide whether you agree, and c) learn from it.

For Critics

There is, of course, another side to this coin. How can you be a useful critic, rather than a smart arse know all?

1. Be Nice

Find something you can genuinely enthuse about. Sometimes, that will require you to go the extra mile in terms of how much time you spend on it, but there will always be something.

2. Read it with some care and attention

Read the piece. Seriously. Don’t be that person who turns up to the feedback session who hasn’t done the reading. Even worse, don’t be that person who pretends they’ve done the reading, and can only give the most bland unhelpful feedback ever. Obviously, even budding writers have lives and shit happens, so sometimes you just don’t have the time. Everyone understands that and forgives. But only once. The writer has spent a lot of time producing this, so the least you can do is be respectful and read the damn thing. Even if you hate it.

3.Remember whose writing it is

Don’t give loads of advice about how to change it. It’s not your WIP, remember, it’s theirs, and you may have completely misread their intentions. Frame your feedback in terms of how it came across to you, and then let the writer decide what should follow from that.

4. Give the writer the benefit of the doubt.

Engage your brain when reading the submission and then when feeding back in the group. If, as is likely, the submission is a section of a longer piece, be wary of droning on about how there were too many character names, you didn’t know how they fitted together, or what their relationships were. Give the writer the benefit of the doubt. Almost certainly, the sections either side of the submission will answer your questions. The writer is often asking the reader to do some work, puzzling out the connections. You know, like someone who reads a lot of fiction. They are paying you a compliment and you should return the favour.

When it comes to meaning, in my opinion 75% of the meaning of any 500 word passage comes from the 500 words that precede it and the 500 words that immediately follow it. Notwithstanding the point above, the submission should be able to stand on its own two feet, with its merits clear for all to see. Please note: all percentages in this blog are meaningless, or at best, vague substitutes for words like “very”, “some”, “most” etc.

5. Give the writer the benefit of the doubt again

This is with particular reference to character. It’s pretty difficult to make meaningful judgements about the authenticity of characters in the first few pages after they are introduced. All the reader knows about a character is what the writer has chosen to tell you (or show you). So if a character jars with you, don’t say “this character would not behave like that”, because you really can’t know that. What you really mean is “The stereotypical character I’m referencing in my head wouldn’t behave like that.” And that leads you into the revolutionary idea that the thought or action or speech you objected to, might well be a deliberate act on the part of the writer, designed to build up a picture of an unusual, complex, messy, unpredictable character. Because that’s what people are like.

On the other hand, there comes a point deep into the book, where you know enough about the character to make that kind of judgement fairly and helpfully. It’s after about 120 pages, roughly. (not)

6. Do As You Would Be Done To

Most importantly, remember that the people whose work you are critiquing will soon be doing the same to you. Another, more cynical, reason for rule 1 in this section.

Please note: every item in the list of advice above can be ignored. There are no rules. Only you will recognise which bit applies to you and it will be different for everyone. The only bit that that doesn’t apply to is this final nugget of wisdom:

Enjoy it. Recognise the luxury of having found a group of people who, like you, are similarly obsessive about reading and writing and then talking about it. It’s a gift beyond price – even if you’re paying an arm and a leg for it. Whether you desperately dream of being published, or would just like to write something for yourself and your family, sharing your work will help.